Apple’s pivot to services: What it means for telcos

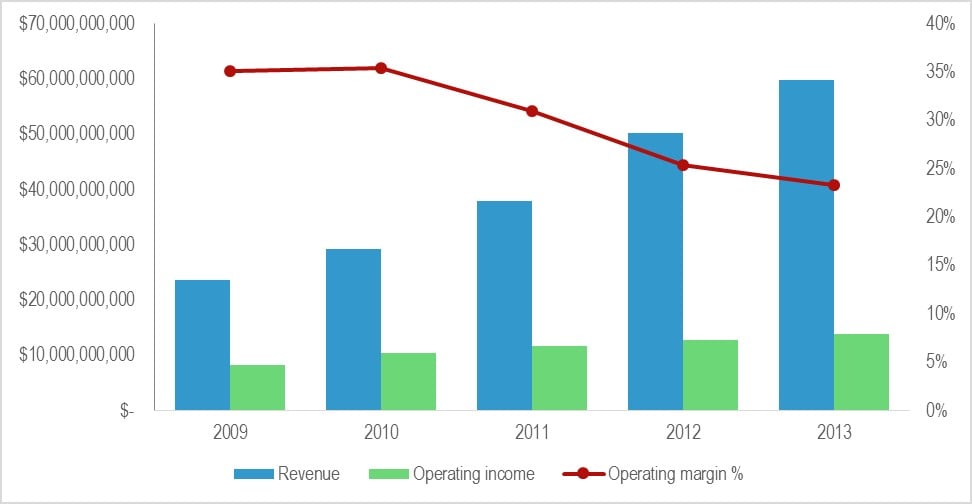

With iPhone sales apparently peaking, Apple is looking to double its revenue from services over the next four years to approximately US$50 billion, taking it deeper into adjacent markets, such as entertainment, financial services and communications. However, Apple trails behind Google in developing artificial intelligence and needs to extend the reach of its services to capture more behavioural data. If Apple decides to decouple more of its key services from its hardware, that would have major ramifications for Google, Amazon, Facebook and many of the world’s leading telcos.