Cloud native: Just another technology generation?

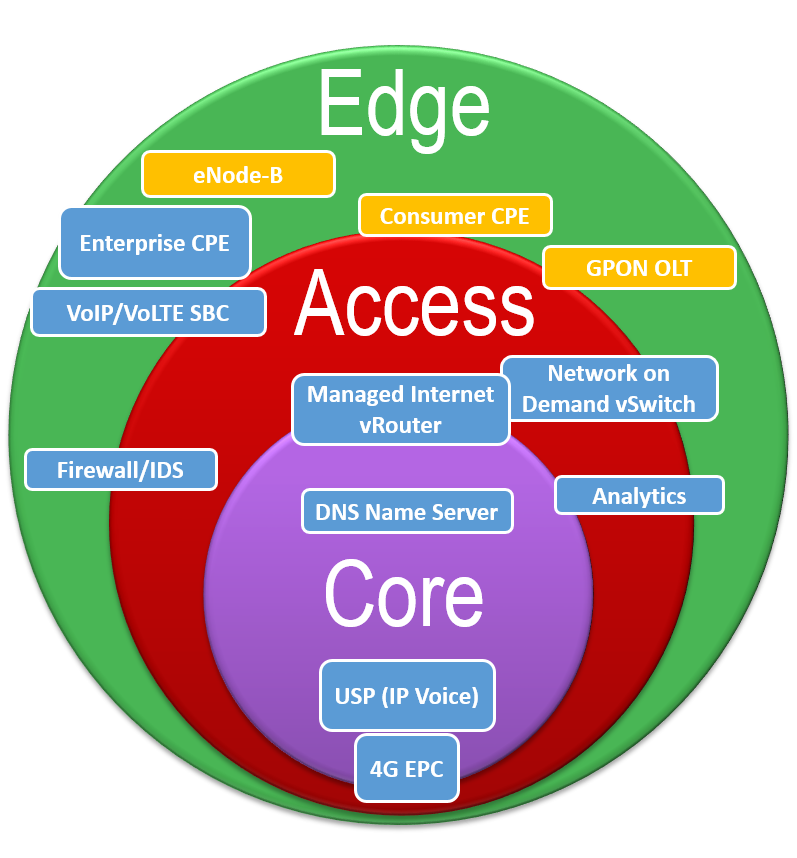

Cloud native networking offers operators a promise of efficiency, automation and innovation to underpin their future in the coordination age. But it should also mean a new operating model, new skills and organisation that few feel they are ready for.