Seven Tough CEO Questions – Telco 2.0 Update

We’ve identified seven questions that are fundamental to telcos’ forward success, and compiled some of our recent research that helps address them.

We’ve identified seven questions that are fundamental to telcos’ forward success, and compiled some of our recent research that helps address them.

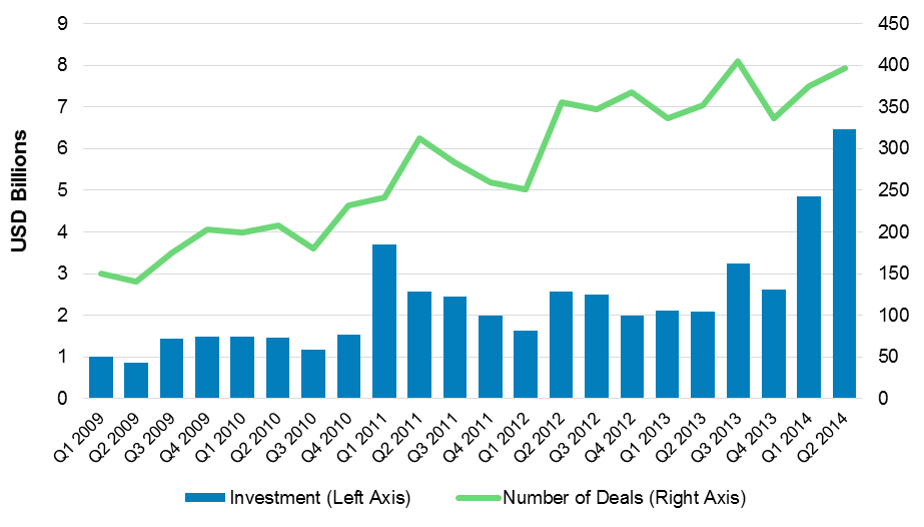

STL Partners published the inaugural version of our Digital Investment Database in early July, and we’ve now issued our first update, including a brief overview of Softbank’s acquisition of ARM and Verizon’s purchases of Yahoo! and Fleetmatics.

Dialog Axiata in Sri Lanka has developed a fast growing API platform that engages developers significantly more than plays by big telcos like AT&T, Orange and Vodafone relative to its scale. How has it achieved this and driven monetisation, innovation and efficiency within the company? And what is next?

M&A and majority investment are key tools in building digital businesses. But are telcos actively investing? We look in detail at SingTel, Telstra and Verizon, which have committed significantly to digital investment to extend their businesses. We also discuss why most European operators lag their Asia-Pac and North American peers. Our analysis is based on the newly-developed STL Partners Digital Investment Database, which tracks investments by 22 leading service providers.

Becoming a Telco Cloud Service Provider (TCSP) is a new vision for the future of telecoms operators, which promises hugely improved agility, a fundamentally new business model, new services, and new growth. What is this vision, how would it work, and how can it overcome the barriers to change that have thwarted most previous efforts?

The mantra of MWC 2016 was “5G, the cloud, and the Internet of Things”. We think that, underlying the buzzwords, there is a more profound reality for telcos. This is that they need to encompass many of the learnings and techniques of the IT industry to transform to a new breed of truly agile player. Fast.

In this analysis we examine the background and trajectory of Telefónica’s high-profile NFV program, how it may evolve, and the implications for other operators on or considering the journey.

The last few years have seen attempts by many leading telecoms operators to refresh their business model and generate new sources of growth and value. Now many digital initiatives are being scaled back. Telefonica and Telenor, two companies in the vanguard of the ‘drive to digital’ have both disbanded their digital organisations. In the first of two reports, STL Partners explores why efforts to yoke platform and product innovation businesses to a traditional infrastructure business have proved so difficult. The financial and operational constraints associated with traditional telecoms – particularly the need for long investment cycles in ‘one-function’ infrastructure – have made achieving the switch to ‘agile digital innovation’ all but impossible. But all that may be about to change and the future could be a little brighter.

Widespread use of open source software is an important enabler of agility and innovation in many of the world’s leading internet and IT players. Yet while many telcos say they crave agility, only a minority use open source to best effect. We examine the barriers and drivers, and outline six steps for telcos to safely embrace this key enabler of transformation and innovation.

We believe that the global telecoms market is approaching a critical moment of change, as strategic drivers and enablers are combining to open the door to a fundamental shift in the industry. We show how and why with highlights of our recent research, and set the scene for a new vision for Telco 2.0 – what telcos should be in the future, and how to get there.

We outline our ‘proxy model’ for valuing Digital Services Businesses, based on current best practice, which has significant advantages over traditional approaches. This report, our second of two on valuation, gives a worked example of a telco’s digital business in Asia that is already worth $1bn, and includes an analysis of approaches being taken by some leading telcos today.

Digital initiatives are an important part of the telecoms growth story. However, because they are so different to the traditional telecoms business, they require different performance metrics: a digital dashboard. In this report, we examine the importance of metrics in shaping business performance, explore the contribution of metrics to 3 telco digital success stories, and reveal how a cutting-edge approach to metrics is driving digital execution at Telkom Indonesia.

STL Partners’ industry transformation analysis, including a recent global survey of telco executives, suggests operators’ digital ambitions are rising fast but, given 9 substantial implementation challenges, too little is currently being done to engender successful industry-wide business model transformation. We also look at the lessons from NTT DoCoMo, one of the operators that has made the most overall progress towards a ‘digital’ model.

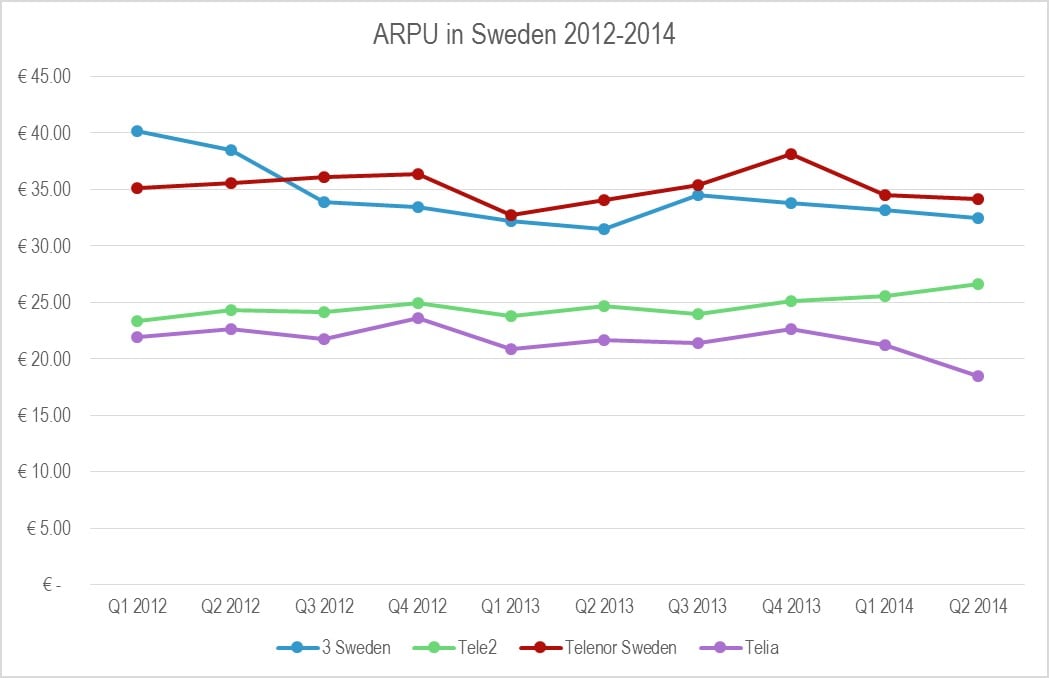

A small and surprising set of national operators are delivering outstanding performance in the challenging European market. Our analysis shows how they’re achieving differentiation with smart strategies that target the hottest customer need, and the considerable ramifications for the rest of the market.

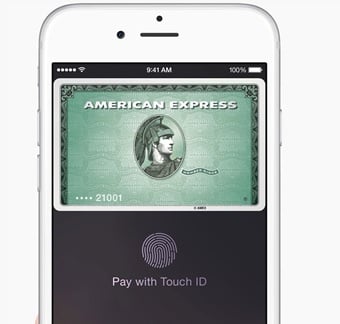

The unveiling of Apple Pay and unravelling of Weve (the UK operators’ payments venture) looked like bad news for telcos’ ambitions in mobile payments in some markets, and highlighted challenges to Google and others’ models. Yet there are already successful telco models and favourable market trends that telcos should exploit. So what are the opportunities now?

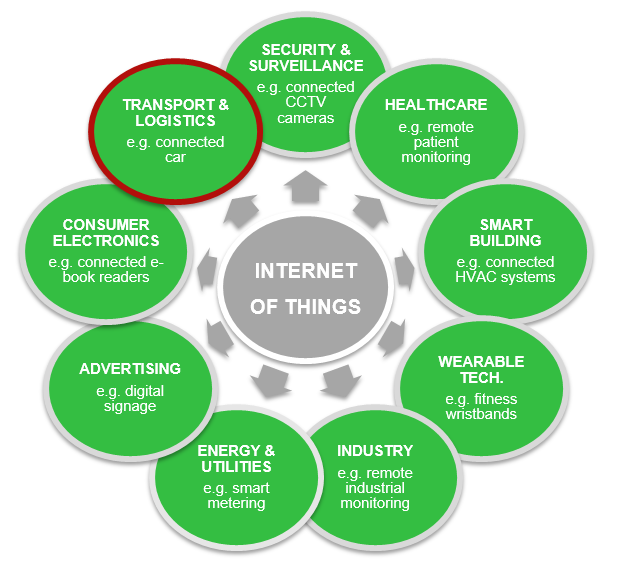

Connected cars are set to revolutionise the automotive industry as we know it, turning the car into the ‘ultimate mobile device’ and driving the growth of M2M in a big way. With Apple, Google, telcos and many others in the chase, we analyse the growth drivers, value chain, and key battles for control of this increasingly complex ecosystem, and outline a new connected car services framework.

A launcher is a customizable home screen for an Android device that allows users to reorganize, customize and interact with their device. Launchers are gaining popularity, with Facebook, Google, Twitter and Yahoo all having either acquired or developed their own versions, but the market is fragmented with different launchers providing different functionality, services and monetization methods. Our latest analysis shows how telcos should seek to explore this area to help them establish more relevance in the digital ecosystem.