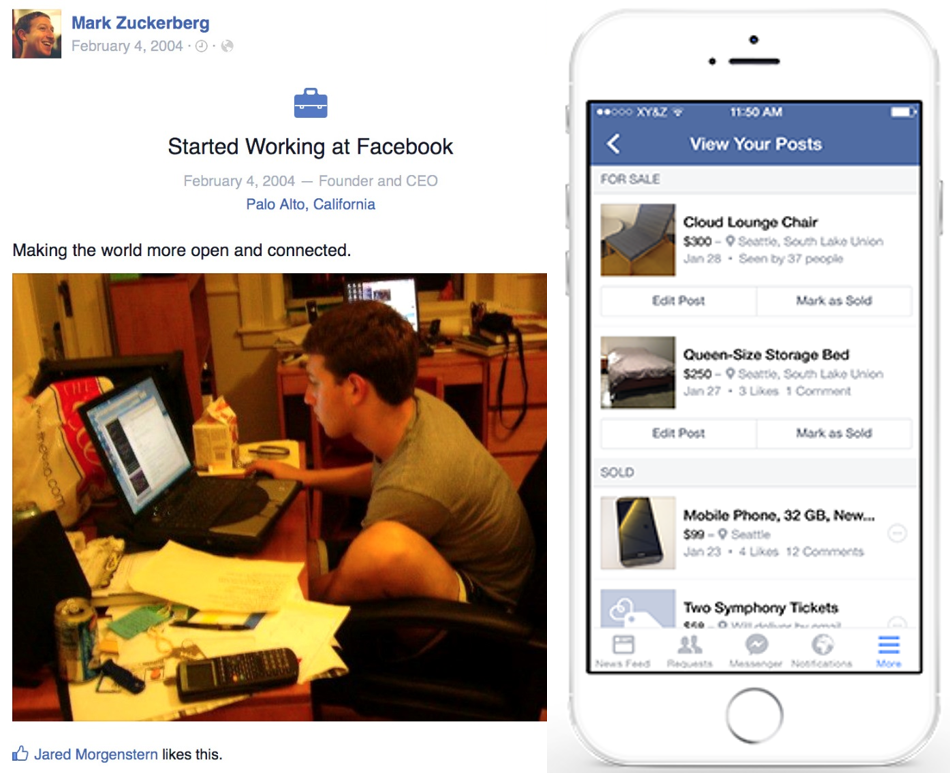

Facebook: Telcos’ New Best Friend?

Facebook has changed substantially since we first analysed the company in 2011. In our latest major report we explore the accuracy of our 2011 predictions regarding users, revenue and strategy. We also examine Facebook’s current aspirations and challenges and explain why, where and how operators should be working with Facebook to build value.