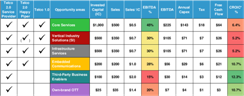

MobiNEX: The Mobile Network Experience Index, H1 2016

The quality of experience delivered by operators’ mobile data networks is a key indicator of their current performance, and a foundation of their future prospects in digital. Our MobiNEX ranking, updated this week for H1 2016, shows how 80 operators in 25 countries compare. How does your telco stack up?