Telco plays in live entertainment

Live entertainment is evolving fast, as greater connectivity and digitisation allows for new experiences for both the audience at the venue and the people watching online. How can telcos play a more valuable role?

Live entertainment is evolving fast, as greater connectivity and digitisation allows for new experiences for both the audience at the venue and the people watching online. How can telcos play a more valuable role?

US President-elect Donald Trump made many statements during the campaign, but now that he has won the election what will his administration do? In this report we look at five key areas for the TMT sector and analyse how we think Trump’s presidency is most likely to impact them.

For the past 30 years, telecoms regulation has largely been designed to keep the market power of incumbent telcos in check. Now, the growing maturity of the market, the massive power of global digital players, and the pressing need for more investment are combining to prompt a regulatory rethink. How should telcos and regulators change their approaches to accelerate the cycle of growth and innovation?

The spread of 3G and 4G mobile networks in Africa and developing Asia, together with the growing adoption of low cost smartphones, is helping Facebook, YouTube, Netflix and other global online entertainment platforms gain traction in emerging markets. But some major international telcos, such as Vodafone and MTN, also have well-established and multi-faceted online entertainment offerings in Africa and developing Asia. How robust are these telcos’ entertainment services? Can they fend off the mounting challenge from global Internet players? What is working for Vodafone India and MTN and what needs a rethink?

Some of the world’s largest telcos see the fast-growing demand for online entertainment as a golden opportunity to shore up their revenues and relevance. BT, Telefónica and Verizon are among the major telcos pumping billions of dollars into building end-to-end entertainment offerings that can compete with those of the major Internet platforms. But how well prepared are telcos to respond to the forces set to disrupt this fast-changing market?

Online entertainment is increasingly dominated by 5 big platforms but 6 forces are likely to shape the market going forward and could have profound effects on the dominant platforms. We analyse the relative strengths and weaknesses of each player and explore the potential opportunities for telcos to compete and collaborate.

Key trends, tactics, and technologies for mobile broadband networks and services that will influence mid-term revenue opportunities, cost structures and competitive threats. Includes consideration of LTE, network sharing, WiFi, next-gen IP (EPC), small cells, CDNs, policy control, business model enablers and more. (March 2012, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

Trends in European data usage

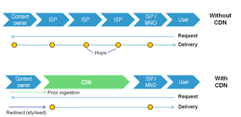

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) are becoming familiar in the fixed broadband world as a means to improve the experience and reduce the costs of delivering bulky data like online video to end-users. Is there now a compelling need for their mobile equivalents, and if so, should operators partner with existing players or build / buy their own? (August 2011, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

Telco 2.0 Six Key Opportunity Types Chart July 2011

‘Net Neutrality’ has gathered increasing momentum as a market issue, with AT&T, Verizon, major European telcos and Google and others all making their points in advance of the Ofcom, EC, and FCC consultation processes. This is Telco 2.0’s input, analysis and recommendations. (Sept 2010, Foundation 2.0, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

A write up and analysis of new research plus participants’ and speakers’ views at the May 2009 Telco 2.0 Executive Brainstorm exploring the challenges of the broadband video crisis. (May 2009, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).