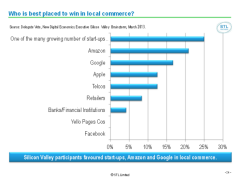

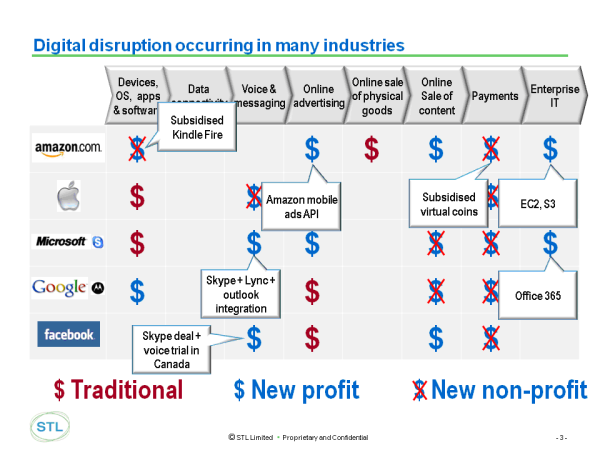

Telcos, Internet and technology players, banks and payment networks have disruptive $billion opportunities to act as intermediaries / enablers in mobile commerce and personal cloud services, based on the appropriate use of customer data. This report is a unique and comprehensive strategic guide for success in these roles. It analyses the strategies of the main and cutting-edge players, and outlines key success factors in designing and delivering customer propositions, technology, organisation and value network strategies. It also includes evaluations of the related strategic opportunities of ‘raw big data’, professional data services, and internal data use, and a business model showing how one type of candidate for the intermediary role, a telco, could grow profitable new revenues equivalent to c.$50Bn (5% of existing core revenues) within five years. (October 2013, Dealing with Dsiruption Stream). Telco 2.0 Transformation Index Small