How telcos can make the world a safer place

With the rollout of 5G, the telecoms industry could coordinate the development of early warning systems to mitigate the impact of pollution, wildfires, floods, infectious diseases and other threats.

With the rollout of 5G, the telecoms industry could coordinate the development of early warning systems to mitigate the impact of pollution, wildfires, floods, infectious diseases and other threats.

Telcos are well placed to enable the healthcare sector to meet the rising demand for secure and reliable in-home monitoring and treatment for the elderly and infirm.

Digital solutions supporting consumer health and wellness are proliferating, driven by the take-up of wearables and a growing supply of data from consumers, advertisers, insurers and healthcare providers. In this report we explore the ecosystem, and discuss the key players and opportunities, the likeliest areas for disruption, and the potential opportunities for telcos, as well as presenting case studies of the digital health strategies of Google, Apple and Microsoft.

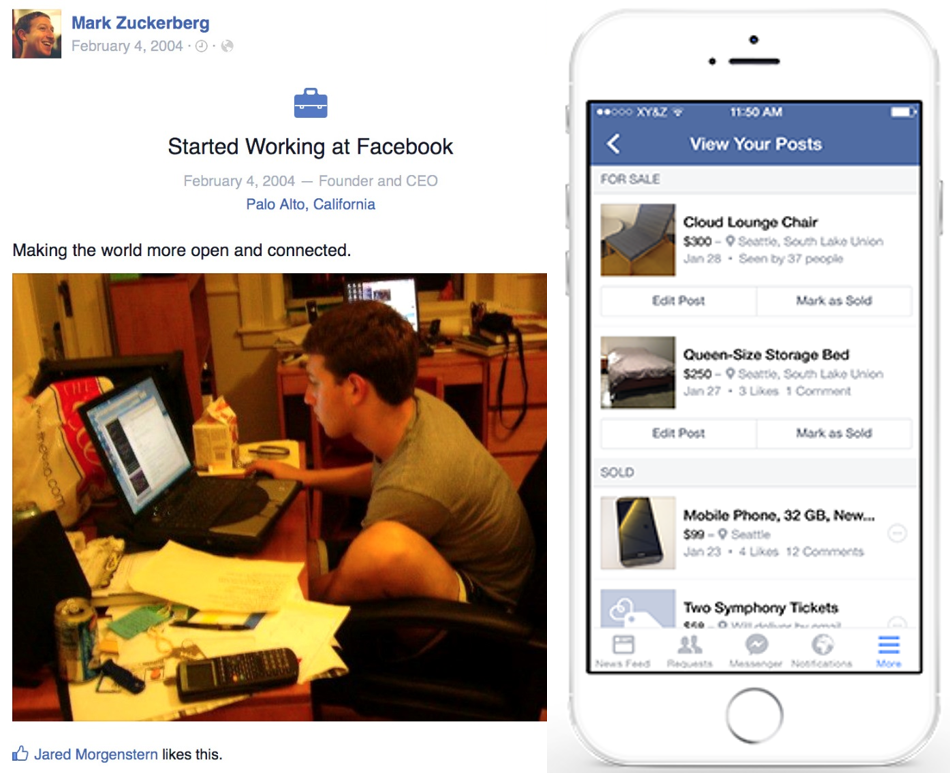

Facebook has changed substantially since we first analysed the company in 2011. In our latest major report we explore the accuracy of our 2011 predictions regarding users, revenue and strategy. We also examine Facebook’s current aspirations and challenges and explain why, where and how operators should be working with Facebook to build value.