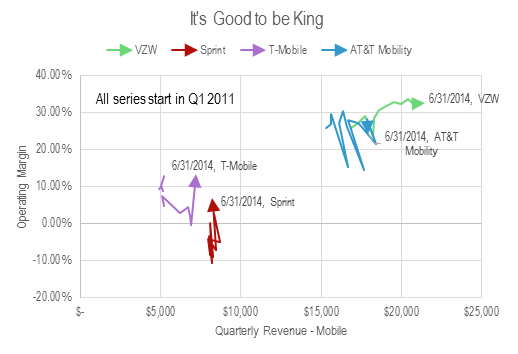

Free-T-Mobile: Disruptive Revolution or a Bridge Too Far?

Free’s shock bid for T-Mobile USA will stretch its finances and management capacity to the limit. Can Free’s package of tactics, technology, and procedures work in the US context?

Free’s shock bid for T-Mobile USA will stretch its finances and management capacity to the limit. Can Free’s package of tactics, technology, and procedures work in the US context?

Key trends, tactics, and technologies for mobile broadband networks and services that will influence mid-term revenue opportunities, cost structures and competitive threats. Includes consideration of LTE, network sharing, WiFi, next-gen IP (EPC), small cells, CDNs, policy control, business model enablers and more. (March 2012, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

Trends in European data usage

Regardless of business strategy, the development of ‘Smart Pipes’ – more intelligent networks – will be a key driver of shareholder returns from operators. Smarter networks will also benefit network users – upstream service providers and end users, and operators, and their vendors and partners, will need to compete to be the smartest. What are they, why are they needed, and what are the key strategies employed to develop them? (February 2012, Foundation 2.0, Future of the Networks Stream).

Facebook user saturation bubble chart

The telecoms industry often puts so-called OTT (over-the-top) players like Google and Facebook at the forefront of its concerns, as they pose new competition for services and applications. But what about encroachment of companies “underneath” the telcos, displacing them from their core asset, the network? Telco 2.0 examines the strategic threats and opportunities from wholesale providers, outsourcers and government-run broadband networks. (January 2012, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

UTF Image Jan 2012

An analysis of the status of LTE, the next generation of wireless network technology, including a round-up of early operator trials, and views on prospects for key vendors by Telco 2.0 partners Arete Research. (December 2011, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

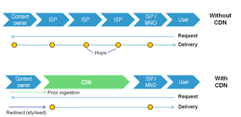

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) are becoming familiar in the fixed broadband world as a means to improve the experience and reduce the costs of delivering bulky data like online video to end-users. Is there now a compelling need for their mobile equivalents, and if so, should operators partner with existing players or build / buy their own? (August 2011, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

Telco 2.0 Six Key Opportunity Types Chart July 2011

To some, LTE is the latest mobile wonder technology – bigger, faster, better. But how do institutional investors see it? An in-depth perspective from new Telco 2.0 partners, Arete Research. (Guest Executive Briefing, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream, Aug 2009).

A write up and analysis of new research plus participants’ and speakers’ views at the May 2009 Telco 2.0 Executive Brainstorm exploring the challenges of the broadband video crisis. (May 2009, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

This briefing summarises key outputs from a recent STL Partners research report and survey on Online Video Distribution. It considers the evolution of the key technologies, and the shifting industry structures, business models and behaviours involved in content creation, distribution, aggregation and viewing.