Can telcos compete in the new TV market?

Providing TV and video content can still be a profitable business, but only if telcos play to their strengths by focusing on aggregation, distribution and recommendations.

Providing TV and video content can still be a profitable business, but only if telcos play to their strengths by focusing on aggregation, distribution and recommendations.

Fixed Wireless Access (FWA) is becoming a mainstream proposition across urban, rural and developing environments. 5G is an important enabler but not the only one. Unusually, FWA will benefit almost all market players – fixed and mobile operators, vendors, investors and regulators. This report contains our 5-year forecast and recommendations for all players.

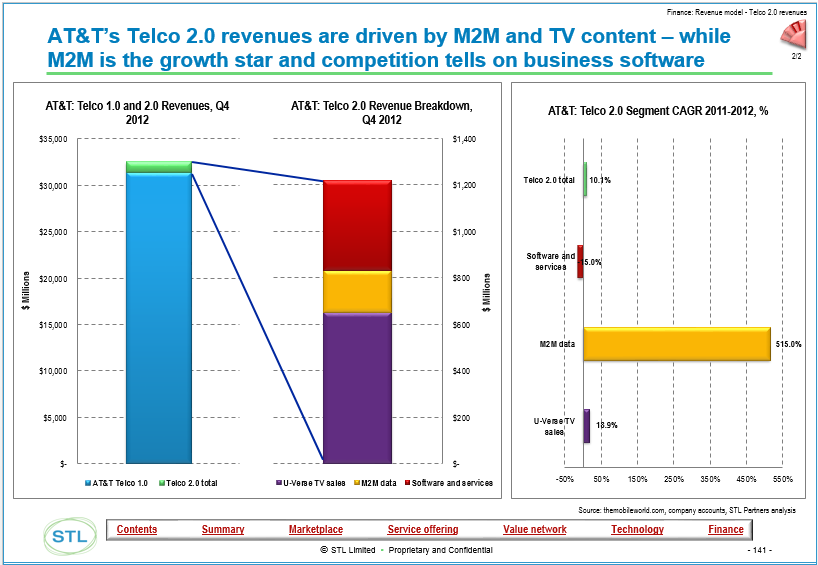

Verizon and Comcast have invested in high bandwidth fibre and cable networks, whereas AT&T has until recently focused on U-Verse, an IPTV play. Which strategy is winning out and why? The answer is surprising and may transform the US and other markets, and there are parallels with Apple and Samsung’s ‘deep value’ strategies of investing in assets that are hard to replicate.

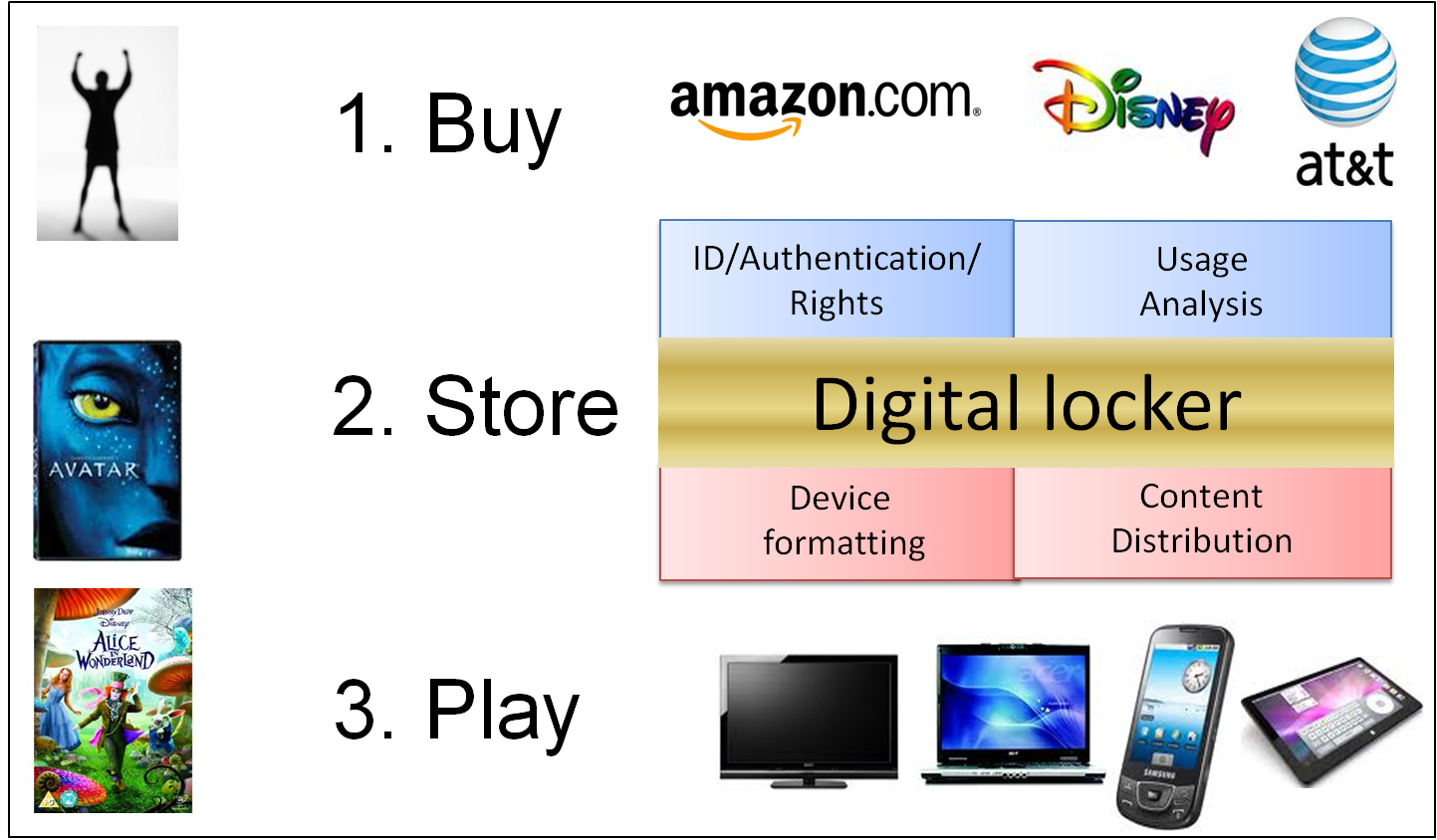

Telco assets and capabilities could be used much more to help Film, TV and Gaming companies optimize their beleaguered business model. An extract from our new 38 page Executive Briefing report examining the opportunities for ‘Hollywood’ and telcos. (Executive Briefing, August 2010)