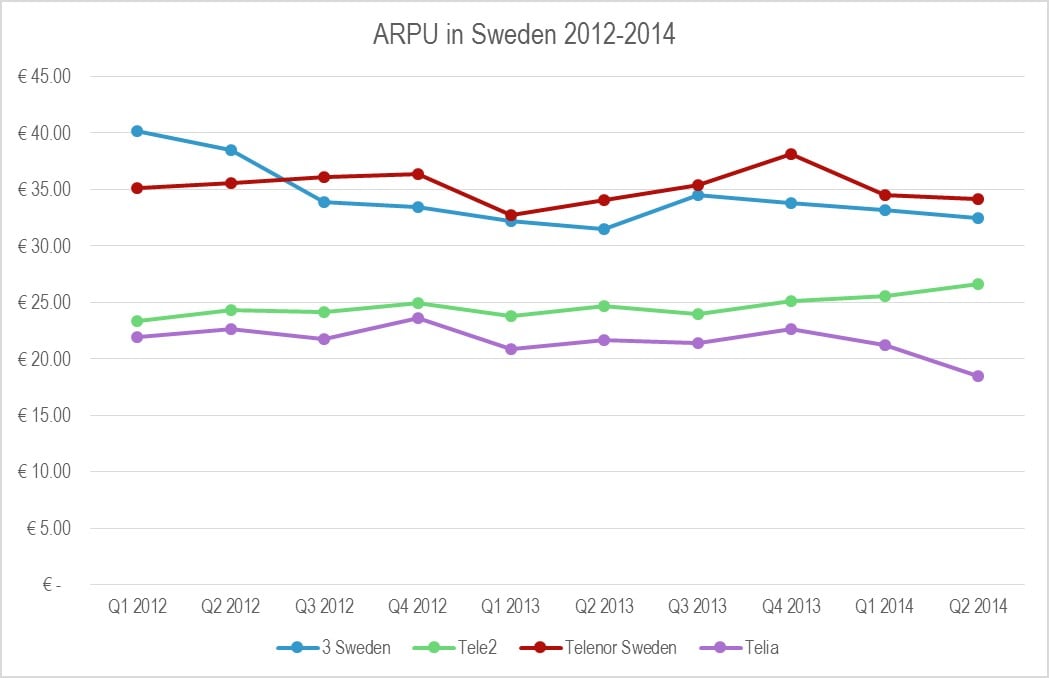

Winning Strategies: Differentiated Mobile Data Services

A small and surprising set of national operators are delivering outstanding performance in the challenging European market. Our analysis shows how they’re achieving differentiation with smart strategies that target the hottest customer need, and the considerable ramifications for the rest of the market.