Telco network edge computing: Lessons from early movers

Drawing from the experience of Lumen, SK Telecom, Telefónica, Verizon and Vodafone, this report identifies the steps, partnerships and expectations of a successful telco edge strategy.

Drawing from the experience of Lumen, SK Telecom, Telefónica, Verizon and Vodafone, this report identifies the steps, partnerships and expectations of a successful telco edge strategy.

To date, discussions of the benefits to telcos of NFV and SDN have mainly focused on reducing operating and capital costs, while the impact on future telco revenues has been somewhat sketchy. In order to fill this gap, this report outlines a comprehensive set of potential new “telco cloud” services, and forecasts associated revenue growth.

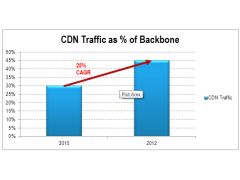

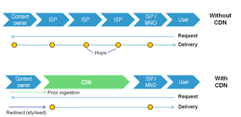

Changing consumer behaviours and the transition to 4G are likely to bring about a fresh surge of video traffic on many networks. Fortunately, mobile content delivery networks (CDNs), which should deliver both better customer experience and lower costs, are now potentially an option for carriers using a combination of technical advances and new strategic approaches to network design. This briefing examines why, how, and what operators should do, and includes lessons from Akamai, Level 3, Amazon, and Google. (May 2013, Executive Briefing Service).

CDN Traffic as Percentage of Backbone May 2013

Key trends, tactics, and technologies for mobile broadband networks and services that will influence mid-term revenue opportunities, cost structures and competitive threats. Includes consideration of LTE, network sharing, WiFi, next-gen IP (EPC), small cells, CDNs, policy control, business model enablers and more. (March 2012, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

Trends in European data usage

CDN 2.0: Event Summary Analysis. A summary of the findings of the CDN 2.0 session, 10th November 2011, held in the Guoman Hotel, London

CDN 2.0: A Summary of Findings of the CDN 2.0 Session Presentation

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) such as Akamai’s are used to improve the quality and reduce costs of delivering digital content at volume. What role should telcos now play in CDNs? (September 2011, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

Should telcos compete with Akamai?

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) are becoming familiar in the fixed broadband world as a means to improve the experience and reduce the costs of delivering bulky data like online video to end-users. Is there now a compelling need for their mobile equivalents, and if so, should operators partner with existing players or build / buy their own? (August 2011, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

Telco 2.0 Six Key Opportunity Types Chart July 2011

Telenor’s new ‘Mobile Business Network’ integrates SME’s mobile and fixed phone systems via managed APIs, providing added functionality and delivering greater business efficiency. It uses a ‘two-sided’ business model strategy and targets the market via developers. (December 2009)

A write up and analysis of new research plus participants’ and speakers’ views at the May 2009 Telco 2.0 Executive Brainstorm exploring the challenges of the broadband video crisis. (May 2009, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream).

The impact of the launch of BBC’s online video service “iPlayer” on the UK DSL industry based on live network data. (Feb 2008)